THE CAPTURE OF SCHOPPEN

By Max Poorthuis · March 14, 2018

By mid-January 1945, the Germans no longer had the initiative of attack in what became known as the Battle of the Bulge. Lack of fuel forced the Germans to simply abandon their vehicles. Roads were clogged and blocked with snow “knee-deep on the level and drifted to two to three times that depth where the wind could get at it.” Weather conditions were horrific. Temperatures dropped well below freezing, and clouds of snow made it impossible to see farther than fifty yards. Wet clothes froze on the men, there was a shortage of blankets and it was nearly impossible to keep socks dry. Men were coming down with bad colds and were developing frostbite. Non-combat diseases outnumbered combat casualties four to one. To make matters worse, the terrain, which comprised a series of high ridges and deep draws (usually heavily wooded), was almost impossible to pass through.

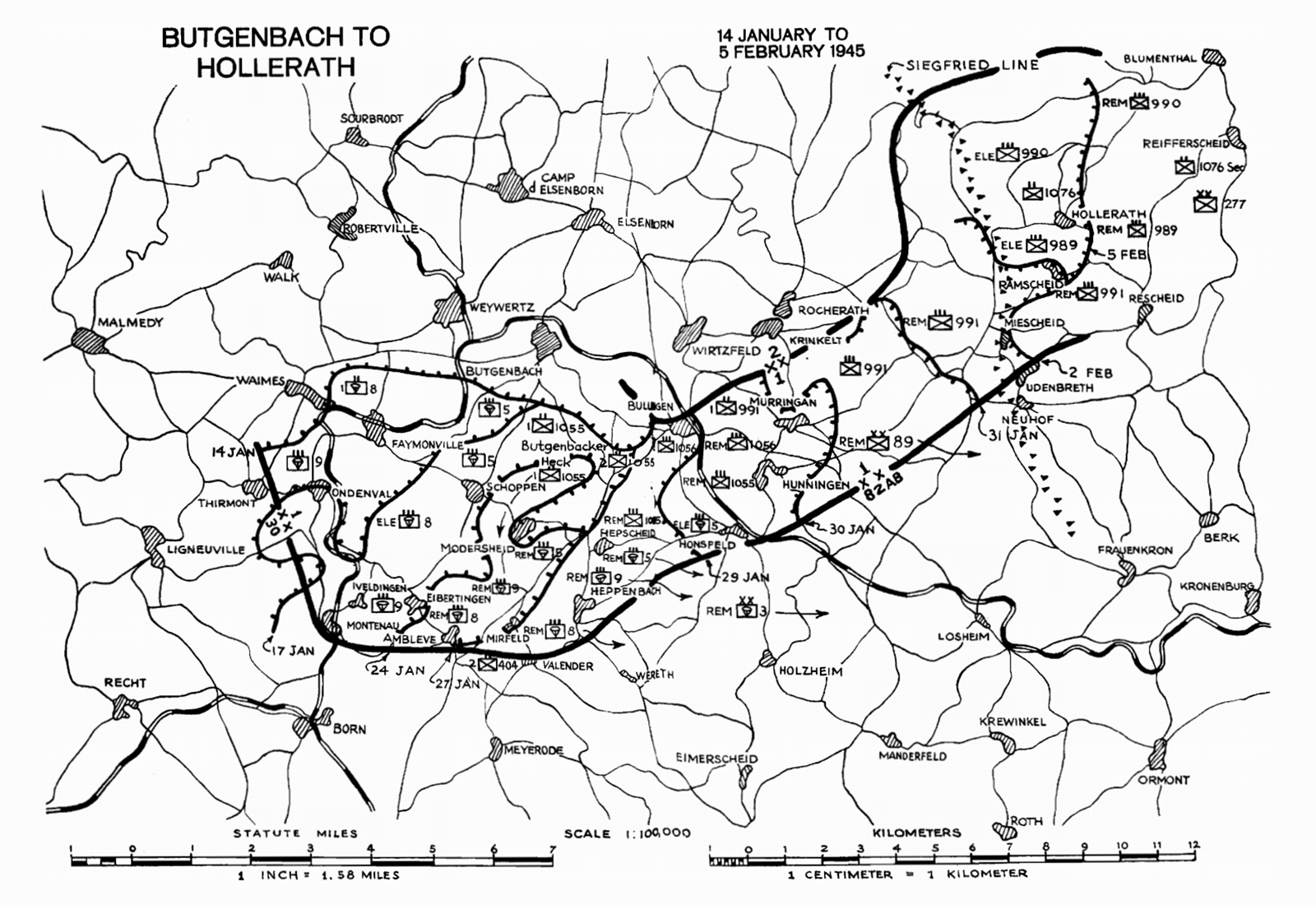

After capturing Faymonville, Belgium, on January 15, 1945, the 16th Infantry Regiment began a large sweep aimed at clearing the territory between there and Bütgenbach. The regiment’s next objective was the quiet, peaceful village of Schoppen—a mile southeast of Faymonville—which was defended by German paratroopers of Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 8.

Once Faymonville was cleared, the 2nd Battalion, 16th Infantry was ordered to continue the advance and seize Schoppen, but the battalion stumbled upon heavy resistance in a wooded area halfway to the village. The following day, no further effort was made to capture Schoppen. Instead, the 1st Battalion positioned itself west of the town. At daybreak on the 19th of January, the 3rd Battalion eventually jumped off on the attack for Schoppen under “the worst weather encountered by the 16th during all its campaigning in World War II.” I and L Companies were to capture the village itself, while K Company’s objective was to seize the high ground 500 meters south of the village. Two platoons of M Company supported the attacking units with heavy weapons, and M Company’s mortar platoon provided covering fire. Also supporting the attack were four M10 tank destroyers of the 634th Tank Destroyer Battalion and five Sherman medium tanks of the 745th Tank Battalion.

Elements of I Company were the first to reach the outskirts of Schoppen. The enemy troops in Schoppen and in the small woods just northwest of the village were quickly cleaned out, and at 1057 hours the 1st Infantry Division’s G-3 operations journal reported “SCHOPPEN all clear except for a few buildings.” As it turned out, the enemy was caught completely by surprise and in most cases offered but light resistance. The I Company history noted: “While exhausting from a physical standpoint, the weather, in the final analysis aided in the capture of Schoppen. The enemy had figured that no attack would be made under such conditions and let his guard down.”

After K Company secured the high ground to the south of Schoppen, its 2nd platoon was sent to clean out some houses in front of L Company’s position. At that time, the Germans counterattacked with approximately one hundred infantrymen and three self-propelled guns, coming in from the south and east. Artillery fire was brought down on the advancing enemy troops, quickly beating off the attack. Meanwhile, the 1st Battalion attacked south toward Elbertingen, and the 2nd Battalion pushed south to the Amblève River.

A house-to-house search for German snipers in Schoppen, Belgium.

At the end of the day, Schoppen was securely held, and the men of the 3rd Battalion dug in to hold their ground. In a day of fighting, the regiment lost sixteen enlisted men and one officer, and many more were wounded.

For the 16th Infantry, the Battle of the Bulge was now over. The fighting during January 1945 also marked the beginning of the end for Nazi Germany. Before the end of the month, the German lines had been pushed back to their initial jumping-off point. Having exhausted what few reserves they could put together, the Germans knew that Hitler’s final gamble in the West had failed. The Third Reich was in its death throes, and by that winter’s end, the Allies were across the Rhine.

GET INVOLVED

Your contributions allow current and future generations to better

understand and appreciate the price of freedom.